Nutrition is important in any child’s life. But it is even more critical in a sick child’s recovery. For each individual child, their food needs to be appropriate to their age, size, changing medical condition, attitudes and tolerances. And for some children, the wrong food can be lethal. There can be metabolic disorders, food allergies, malnutrition that needs to be corrected, gastrointestinal diseases, genetic conditions that require very specific nutrients, and a host of other concerns, not always directly associated with the reason they are in the hospital. Babies have an entirely different set of needs, particularly those in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, where their fragile state can change hour to hour.

At Connecticut Children’s, keeping track of every child’s nutritional needs and doctors’ requirements is the job of the Department of Clinical Nutrition Services working in tandem with the Food Services team. Together, they provide the right food for every meal every day for every child in the hospital. Beyond that, they offer outpatient nutritional counseling, eating disorders treatment and weight management programs. It’s a massive, complex, crucial and often unseen component of the hospital. To throw a little light on this vital service, we spent one shift with these teams. Here we share a few snapshots of the hundreds of tasks they undertake each day. All of this work is supported by you and your generous gifts to Connecticut Children’s.

9:00 a.m.

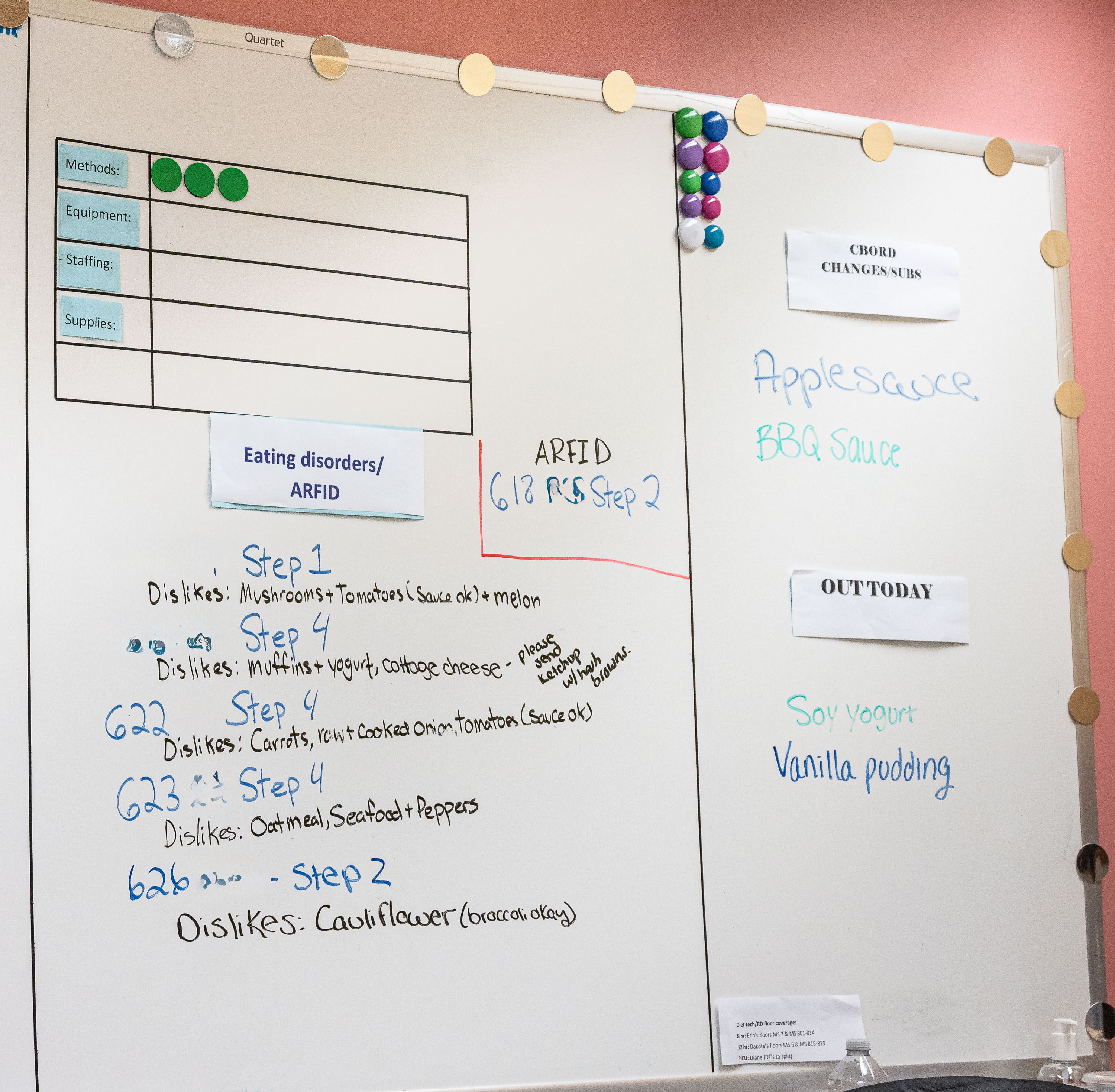

The day begins with a huddle in the hallway next to the kitchen in the basement of the main hospital at 282 Washington Street. Representatives of the nutrition and food service teams are here for the first of two daily huddles, intended to keep everyone coordinated and aware of rapidly changing circumstances. They review the information crammed onto two whiteboards, one on each side of the hall. Today, the huddle is being led by Danny Berube, the manager of the Food Services team. A big, affable man, he goes over the day’s staffing, requirements for children with eating disorders, foods that are on order, food substitutions and children who have been discharged. This last part—patients being discharged and new patients being admitted—makes the process all the more challenging, providing a constantly moving target.

Today, there are 160 children staying in the hospital, each of whom needs a specific set of meals, along with many children who come to the Emergency Department who may need meals. For the Food Service team, supply-chain issues provide their own challenges, and the team frequently has to scramble to find substitutes for a type of food that they were expecting but is stuck somewhere in transit. Once everyone has reviewed the charts, they head off to their respective duties.

9:30 a.m.

Ben Wentworth, a registered dietitian, is on the sixth floor of the hospital, talking with seven-year-old Alyssa P., a bright, outgoing and supremely self-confident girl, going over her choices for meals that day. Ben has a digital tablet in his hand with a page for each child on the floor, listing all the foods that are available for that child, together with notes about any specific considerations. For example, Alyssa has a note in her record that she needs to be on a low-fiber diet. So when she says she wants mac and cheese for lunch, it fits right in. Of course, mac and cheese is not exactly health food, but the registered dietitians and diet technicians make a point of saying you have to meet kids where they are, making the best possible choices they will accept.

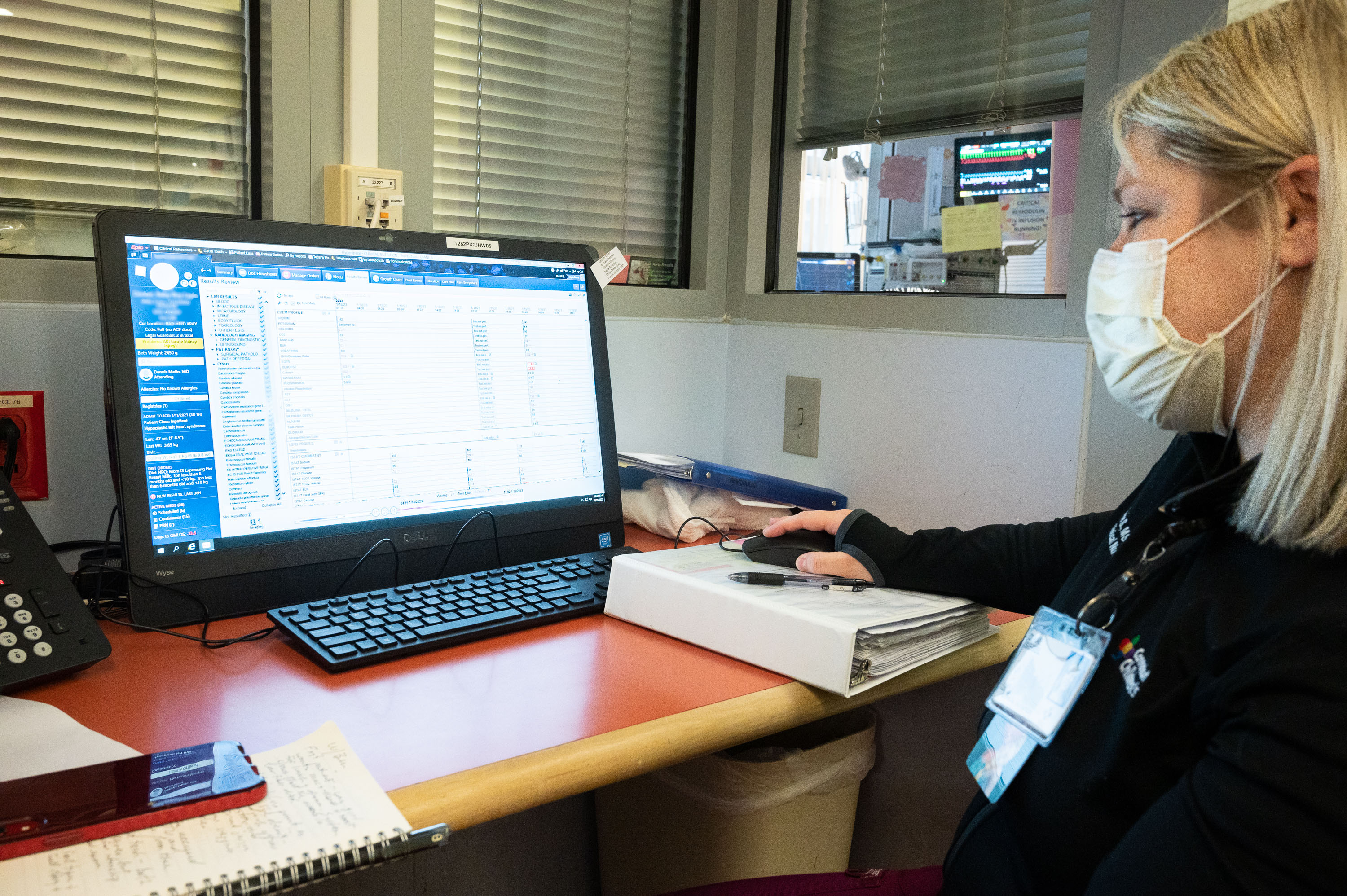

Over the course of the next hour, diet technicians will visit each child on the floor, and other food service and nutrition teams are doing the same on other patient floors and in the Emergency Department (ED). And all of their tablets are connected to a central system that produces menus for the kitchen and keeps track of every child’s needs and requests. Beyond that, registered dietitians are assigned to each inpatient floor and the intensive care units to evaluate children based on each child’s individual medical diagnosis, growth measures, blood test results, labs, scans and other clinical information, to be sure their nutrition is supporting their needs.

10:00 a.m.

In the Formula Room, milk technician Ethan Bamberger, a tall young man with an impressive ponytail stuffed under a hair net, is reviewing all the babies who need formula today and what kind of formula they need. At the grocery store, you might just choose from one brand or another, but the formulas themselves are pretty much the same. Here, however, each baby has his or her own medical and nutrition needs, and may have allergies to some ingredients in formula, so Ethan’s room has shelves and cabinets full of different formulations with different functions—about 100 different products. The recent formula shortage that hit the U.S. created real problems here, but working with their partners in supply chain, the team was still able to provide the correct formula for every baby.

11:00 a.m.

In the kitchen, a Food Service team begins the complicated task of preparing lunch for all the patients in the hospital, including those in the ED. The room is smaller than kitchens in some private homes, and there are four people working in a high-speed, precision ballet. The first batch of meals is going to children who have food allergies or restrictions, where the wrong food could have drastic consequences. The diet technicians, who went room to room earlier taking children’s lunch orders, fed those orders into the digital system. Now the system prints out each order for the food team to prepare.

A team member pulls a slip of paper from the printer, places it on a tray, and then starts selecting specified foods. Those foods are doubled checked by Food Service team members before they go onto a cart for delivery, and then again by a diet technician who goes through everything on the cart, checking each item against the menu for each child. Completed trays go on a cart and are hustled up the patients’ rooms.

11:30 a.m.

Susan Goodine is one of eight registered nutritionists based in the Division of Gastroenterology. Diet education is critical for many GI conditions. There may be many foods a child cannot eat or is unwilling to eat, so figuring out how to meet all a child’s nutritional needs can be especially difficult. She is meeting with the parents of 18-month-old Elora S., a curious girl with a winning smile and a cracker that she is periodically eating while the grown-ups are talking- one of the few things she will eat. Elora was a case of malnutrition and not tracking well along her growth curve. She’s had a work-up to rule out celiac disease and cystic fibrosis, as well as other exams, but the core problem is still elusive. Susan is providing the parents with guidance to help Elora meet her nutrient needs.

“I would say that for 99 percent of the diagnosis we see in GI”, Susan says, “some component of the treatment is nutrition. We treat celiac, inflammatory bowel diseases, constipation, abdominal pain, malnutrition, food allergies, intestinal rehabilitation, irritable bowel syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among many other conditions”

1:30 p.m.

In the Milk Room, things are moving at a breathtaking pace. The two members working on this shift are milk technicians and are almost running from station to station, taking frozen breast milk from the freezer (expressed by patients’ mothers or donated anonymously through a milk bank), mixing formula, heating the frozen milk in highly specialized warming baths, adding nutrients to the milk, then checking and double-checking which milk goes to which baby through an electronic breast-milk scanning system. Because breast milk is only viable for 24 hours once it’s prepared, they do two sessions, the first starting at 6:00 a.m. They work at this pace until noon, then take a break for lunch and come back for another preparation session so babies have milk overnight. Altogether, they will prepare approximately 250 servings of milk today. Again, speed and precision go together, and neither can be compromised.

2:30 p.m.

Registered Dietitian Katherine Sayre is meeting with nine-year-old Javian M. and his mother in the outpatient nutrition office. The team members here meet with children on an outpatient basis who are dealing with poor nutrition, weight issues, food allergies, eating disorders and many other diagnoses that require individualized medical nutrition therapy as part of their treatment plan.

Katherine has met Javian and his mom before; this is a follow-up visit, to see how Javian is faring on the food and exercise plan Katherine has set up for him. She asks Javian what he’s been doing for activity, and he replies that he’s been playing with his VR goggles, which keep him moving while gaming, and he plays basketball on the weekends. Katherine asks whether he is counting his steps, and he is. He says he really wants to learn to play baseball in the spring.

From a nutritional perspective, Katherine wants him to start a multivitamin, cut down on sugary drinks and start using measuring cups to be sure his food quantities are appropriate and consistent. Like all of the members of the nutrition team, she is kind, caring and warm with Javian. For sensitive issues like weight, that is invaluable.

Weight problems and eating disorders have spiked in recent years among children, partly because of the isolation of the pandemic, and having this kind of expert care available is essential.

4:00 p.m.

Beth Chatfield has been working at Connecticut Children’s and its forebearer institutions for 36 years. She is an expert on ketogenic diets, which, it turns out, are remarkably effective in treating seizures from conditions like epilepsy. The diet focuses on foods that help the body use fats to generate energy—butter, oils, meat—as opposed to a more conventional diet of foods that provide glucose, like pasta, cereals, fruits and vegetables. Adopting this sort of diet forces the body to shift its method of operating, entering a state called ketosis. From a biochemical point of view, this is a form of fasting, even though there is plenty of food being consumed. And the body reacts by producing a combination of substances that short-circuit seizures. Researchers are now trying to understand what those substances are and how they work.

It appears the connection between ketosis and seizure relief was known even in ancient times, but it’s only recently that it’s been thoroughly studied and adopted by the medical community. Beth describes one young man who was having 200 seizures a day before starting the diet and having that number reduced to zero by this change.

“This is the best thing I’ve done in my career,” Beth says.

The ketogenic diet has to be designed for each child, and it requires careful monitoring and adjustment, but it can, in many cases, work miracles. It even appears to be effective with some kinds of cancer, including glioblastoma. “It’s incredibly satisfying work to do,” Beth says. That’s a sentiment you will hear from everyone in Clinical Nutrition and Food Services, even as they gear up to do it all again tomorrow.

Latest Articles

Ellie’s Story: How Supporting Connecticut Kids Changes Lives

A Day in the Life: Anesthesiology