Research at the edge of what's possible.

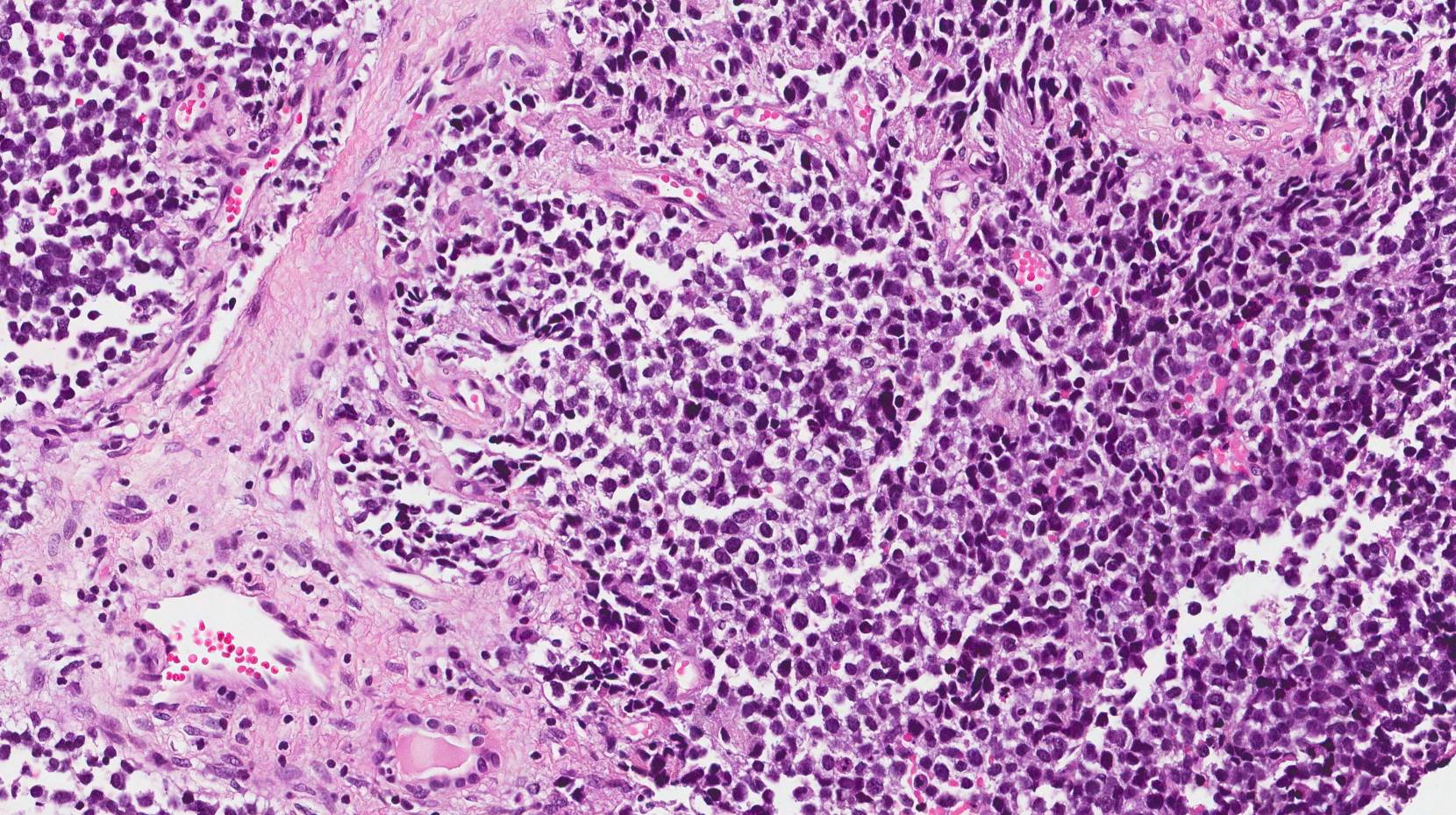

Over the past few decades, treatments for pediatric cancer have improved greatly. Most children now can survive cancers that once had a dire prospect. But there are some cancers that have resisted every attempt at treatment and still take a terrible toll on young lives. One of those is rhabdomyosarcoma, which is a primary tumor involving muscles. For children who are diagnosed with a tumor in only one location, a combination of surgery and chemotherapy can, in many cases, represent a cure. But for too many children, the cancer has already metastasized when they first present, or returns in a more resistant form after initial treatment. In those cases, the prognosis is very grim. Less than 20 percent of those children will survive. Moreover, the prognosis has not improved over the past 30 years for patients who present with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma.

But there may be hope. The Division Head of Hematology and Oncology, Michael Isakoff, MD, is one of the oncologists involved in a groundbreaking research project that is reconsidering what cancer is. And the researchers are taking their model from nature.

Latest Articles

$1 Million Gift from Big Y Supports Connecticut Children's New Clinical Tower and Expanded Pediatric Services

A New Era of Care Begins: Connecticut Children’s Celebrates the Opening of the New Clinical Tower